Photo: courtesy Hooks-Epstein Gallery

When Houston’s FotoFest organizers adopt a theme for the International Biennial of Photography and Mixed Media Art, the topic must be so compelling and relevant as to garner global attention alongside dedicated participation from the city’s leading art museums, art galleries, non-profit art spaces, universities, and civic spaces. Fittingly, the 2016 topic is nothing short of world-changing.

“Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet” is a multi-venue biennial exhibition curated by FotoFest co-founders Wendy Watriss and Frederick Baldwin, and Executive Director Steven Evans. Described as an opportunity to “explore humanity’s relationship with a changing planet,” “Changing Circumstances” showcased a range of artists whose photo-based works draw attention to the realms, realities, and risks of life in the Anthropocene. The exhibition, related programming, and non-thematic exhibitions ran March 12 – April 24, presented by additional city-wide participating venues including Blaffer Art Museum, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Da Camera, and others.

A Houston-based non-profit photographic arts and education organization, FotoFest was established in 1983 for the purpose of promoting international awareness of museum-quality photo-based art from around the world. It is the first and longest running photographic arts festival in the United States and, for more than 30 years, the organization has been building its reputation as one of the leading international photography Biennials.

For the 2016 iteration, the FotoFest team solicited artist’s submissions that “address the needs of our planet and the ways in which we use the world’s resources.” Eschewing simplistic representation or documentation, and setting a broad curatorial definition of sustainability, the goal was to show how art and artists are contributing to change. The result? An exhibition of artworks by 34 artists from nine countries spread throughout Silver Street Studios, The Silos at Sawyer Yards, Spring Street Studios, and Williams Tower Gallery. Through their images, these artists bear witness to the current state of the world- at once beautiful and terrifying-along with a myriad of consequences of our collective impact on delicate ecosystems, consumption of natural resources, unfettered increases in population, and more.

This is not the first time the Biennial theme has addressed environmental issues. In 1994 FotoFest presented “The Global Environment,” in 2004 it was “Celebrating Water: Looking at the Global Crisis,” and 2006 was “The Earth.” However, the 2016 Biennial, “Changing Circumstances,” showcased artworks that go beyond photojournalism or didactic data representation. For example, exhibition highlights included art world heavy-hitters such as Edward Burtynsky, Vik Muniz, and Isaac Julien whose works are on view at The Silos at Sawyer Yards, along with Atul Bhalla’s Ek Rupaya Bada Gilass (One Rupee for a Big Glass of Water), curious “word stacks” by Peter Fend, Lucy Helton’s looming, dystopian views of Earth without life, amongst others.

Burtynsky has long been interested in depicting the drastic “scale and speed of our impact on nature,” often of sites of industry. Muniz, for his series Pictures of Garbage, constructed portraits made of trash of the catadores, or pickers, at Jardim Gramacho, the world’s largest landfill, located in Rio de Janeiro. Julien uses a three-screen film installation to present a cinematic view of human migration, specifically the refugees’ voyages from Libya to Europe in his work WESTERN UNION: small boats.

Throughout the Biennial, an Anthropocene sublime prevailed: from the biodiversity found in National Geographic photographer David Liittschwager’s investigation of one cubic foot of the world to Robert Harding Pittman’s portrayal of the cookie-cutter development sprawl, and Martin Stupich’s dilapidated industrial interiors compared to Mandy Barker’s visual seas of plastic pollution taken from the ocean. Other artists address the physical, historical, spiritual, and political significance of water, and the seeming contradiction of drought and rising sea levels. Amidst the overwhelming magnitude of the truth of their images, and as a product of the environment we have created, we are left to try and comprehend our new normal.

A rather surprisingly poignant group of landscape photographs by Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman, titled “Processed View,” was on view at Williams Tower Gallery. Ciurej describes the series as a cautionary tale. “The destructive and unhealthy changes in farming, food processing and marketing which we have observed during our lifetimes are large and complex,” she says. “We chose to communicate this issue with humor, using familiar foods, ‘bite sizing’ the information. We use the seductive color palettes engineered to make food appealing in order to seduce the viewer into looking: a strategy that seemed more effective than a confrontation with overwhelming research. The reaction to our work often begins with a thrill of familiarity and ends in disgust. We want our viewers to recognize the wonders of food technology, but to consider the health and environmental consequences of industrial foods.”

Included in the exhibition at Silver Street Studios were two artistic considerations of our species’ capacity for growth: German artist Niklas Goldbach’s Land of the Sun and American artist Jamey Stillings’ photo series The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar. Goldbach’s film is focused on the architectural leftovers of California City, one of the world’s biggest failed urban planning projects, while Stillings’ images depict the development of the world’s largest concentrated solar power plant, located in the Mojave Desert. The stark contrast of these developments is compelling, as each proposes its own version of what “renewable” might mean.

Spring Street Studios featured works about our physical and ethereal surroundings. For example, The Atmosphere: A Guide is a selection of atmospheric intersections by the ever-exacting Amy Balkin; Nigel Dickinson’s Smokey Mountain, portrays Cambodia’s Smokey Mountain rubbish dump where 2,000 casual workers (including children) battle pollution, disease, and crime as they pick through the garbage and sort materials sent off to recycling centers; Pablo Lopez Luz presents the multi-faceted significance of Mexico City’s “erratic urban spread” in Terrazo.

With the 2016 Biennial, FotoFest continues its long-time partnership with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) Film Department. Marian Luntz, MFAH curator of film and video, explains that the FotoFest team, including Flo Stone, Founder of the annual “Environmental Film Festival in the Nation’s Capital,” was actively involved in the selections. Stone recommended two of the newest films to screen at the museum: Louie Psihoyos’s Racing Extinction, which draws attention to mankind’s role in a potential loss of at least half of the world’s species, and Luc Jacquet’s documentary Ice and the Sky, about the work of Claude Lorius, who began studying Antarctic ice in 1957 and was the first scientist to be concerned about global warming.

The MFAH is also screening Watermark, co-directed by Burtynsky and Jennifer Baichwal. “And,” Luntz adds, “it made perfect sense for us to debut the museum’s recently restored 16mm film Life-Raft Earth, directed by Robert Frank,” says Luntz. “It was shot in 1969 and profiles activists involved in issues that resonate through the present.”

Luntz goes on to explain her understanding of how artists, and specifically filmmakers, are contributing to positive change around global climate issues. “These films are available in ways that can reach a huge potential audience: film festivals, focused series such as what FotoFest has arranged in Houston, crowd-sourced screenings, television, and streaming online. On most occasions these artists have dynamic websites and a social media presence directing people to become involved in the issues their films address. While a bit overwhelming, it’s our responsibility to engage to the extent we can and participate in global activism.”

New to the usual FotoFest program line-up is Marfa Dialogues/Houston, a partnership with Ballroom Marfa and the Public Concern Foundation. In 2012, Marfa Dialogues, a symposium created to broaden public exposure to the intersections of art, politics, and culture, expanded to consider the science and culture of climate change. As part of this year’s symposium, Matthew Coolidge and Aurora Tang of the Center for Land Use Interpretation were in conversation with Steven Badgett of SIMPARCH. “Overall,” says Coolidge, “the discussion was about inundation (drainage bayou, rivers, the East) and desiccation (salt flats, Las Vegas, the West), and the iterations between.” The day also included additional panel discussions and performances.

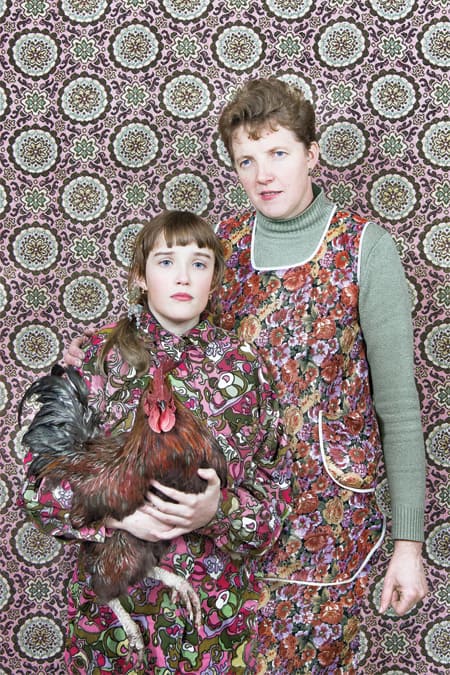

Commercial galleries and additional venues in all corners of the Houston area, reaching even to Galveston, also participated in FotoFest through the presentation of over 100 independently organized exhibitions, some within and some outside of the Biennial’s thematic parameters. Several examples of exhibitions that addressed the preciousness and fragility of life, but not necessarily climate change, include “Dobrostan” at Anya Tish Gallery, a solo exhibition of new and recent photographs by multi-media, Poland-based artist Natalia Wiernik whose portraits of offbeat modern “families” are linked together through a camouflage of extravagant colors and patterns. At David Shelton Gallery was “Sin Héroes,” works by Rodrigo Valenzuela in which the artist “confronts the lack of heroic figures in contemporary culture,” as well as the idealization of fame, fortune, and war, and the associated but unrecognized deaths and sacrifices. Hooks-Epstein presented Julie Brook Alexander’s “Filling in The Blanks,” diptychs of the universally opposing emotions of wanting to hold on to life with a loved one yet, at the same time, needing to let go, and Kathryn Dunlevie’s “Mistick Krewes,” a selection of the artist’s layered images which hint at the historical roots and overlapping contemporary cultures of Mardi Gras.

Somewhat more circumstance-focused exhibitions of FotoFest included “The Mark of Time,” Tim McCoy’s interpretive albumen and palladium prints at Redbud Gallery of cultural remnants, and works by the late Casey Williams at Art Palace in “Back to the Port,” a series of old photographs of ships at port—specifically images of the sun’s reflection on the surfaces of the ships and the water—which he revised with strokes of colored paint.

Although much of contemporary culture is obsessed with the production, dispersion, and consumption of images, the sustainability challenges of the Anthropocene are indeed rooted in our physical surroundings, not in virtual worlds or digitally constructed realities (though even digital activity has a significant carbon footprint). As more organizations and exhibitions like FotoFest consider what roles art and artists play in facing those challenges, a pressing question is surfacing: What good, and perhaps what harm, might more images do? The answers remain to be seen.